While “Adopt a Disability for a Day” wasn’t featured in this October’s Disability Awareness Month event lineup, it was offered at the first “Understanding Disability and Physical Difference Month” celebrated on campus in November of 1971. Students, faculty, and staff were “encouraged to adopt a physical disability of blindness or being in a wheelchair” (Challenge Newsletter November 1972). Participants were assigned a student who was blind or a wheelchair user and were then required to navigate a marked-out course while wearing a blindfold or using a wheelchair. “Dine Blind” from 1972’s event lineup required participants to put on a blindfold and eat a meal “blind” (). Of course, these types of events are problematic by today’s standards. At the time, the Center for Human Understanding housed Student Accessibility Services. The director, Charles Green, explained that the purpose of the events were to “create individual awareness to the barriers faced daily by handicapped students” ().

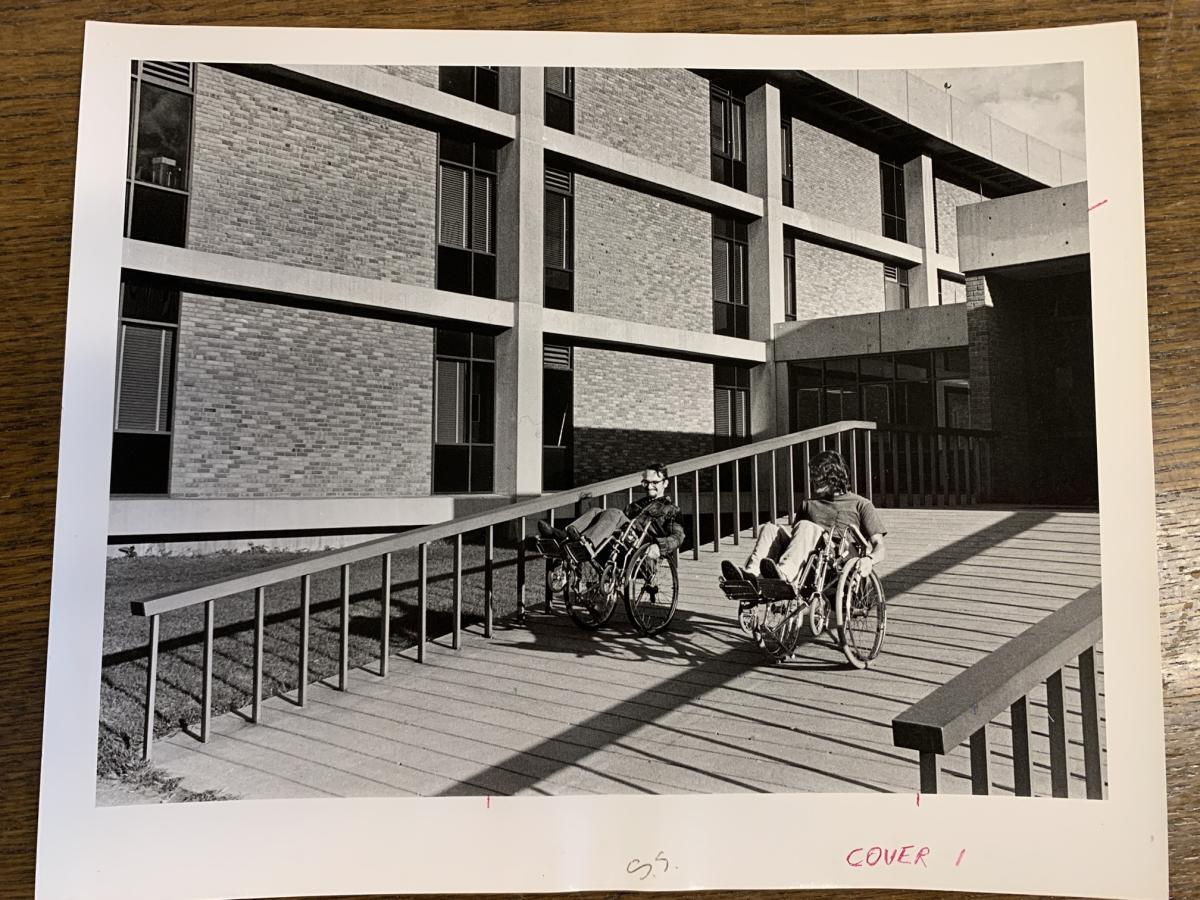

Campus and disability law looked very different in the early 1970s. Student Accessibility Services, then called the Office of Handicapped Student Services (OHSS), had only been in operation for seven years. The first milestone for disability rights, the passing of Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, wouldn’t be passed for another two years. Campus itself was less than accessible, posing a problem for the approximately 400 disabled students on campus at the time (). Rosemary Lips, a coordinator in OHSS, cited a variety of buildings with architectural accessibility issues to wheelchair users such not having ramps or elevators and having restroom doorways that were too narrow (). Understanding Disability and Physical Difference Month began to bring awareness to the accessibility issues on campus and the lived experiences of a population that was overlooked. This focus was in line with the national climate and sentiment regarding disability awareness and protection from discrimination.

The passing of Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act in 1973 prohibited discrimination against individuals with disabilities in the workplace and in any program receiving federal financial assistance. This included universities as well, including ¬È∂π ”∆µ◊Ó–¬◊Ó»´. Though written into law in 1973, the implementation of Section 504 would take much longer. Guidelines to define who would be considered disabled, what constituted discrimination, and how to obtain equal access were slowly forthcoming. By 1977, the disability community was getting tired of waiting on legislation to be passed to enforce the nondiscrimination promised in 1973 ().

In 1977, to expedite the process, a series of sit-ins were coordinated at various federal buildings around the country. The most notable of these took place in San Francisco. “A group of roughly 150 disability rights activists took over the fourth floor of the federal building” stating they wouldn’t leave until Section 504 was fully implemented (). Reminiscent of the civil rights movement and sit-ins of the 1960s, the cross-disability coalition of protestors stayed together in solidarity, eating, sleeping, and living on the fourth floor of the federal building for almost a month. After 25 days, the Section 504 regulations were signed. Kitty Cone, a disability rights activist who took part in the San Francisco sit-in, explained that “before Section 504, responsibility for the consequences of disability rested only on the shoulders of the person with a disability rather than being understood as a societal responsibility. Section 504 dramatically changed that societal and legal perception” ().

These national changes were reflected at ¬È∂π ”∆µ◊Ó–¬◊Ó»´ as well. Gwen Callas, coordinator of Developmental Services for Handicapped Students, explained in a news article that ¬È∂π ”∆µ◊Ó–¬◊Ó»´ would be completing a self-evaluation of all programs and buildings by December 3rd of that year in the Fall 1977 semester. This would be done in accordance with the new regulations that were signed in April due to the sit-ins. Callas explained that ‚ÄúKent is a very receptive community to making changes for people in (wheel) chairs. We‚Äôve moved in some direction but it‚Äôs not enough‚Ķwhat we need to do now is look for accessibility building by building‚ĶIn comparison to other universities, we‚Äôve been working at it a long time. Kent has done a really commendable job, but we still have a long way to go‚Äù ().

Programming for Disability Awareness Week also began to shift away from just creating awareness but also providing assistance and guidance for students with disabilities. In 1978, speakers from various vocational and employment services were invited to campus to speak about accessibility issues in the workplace along with a Career Planning Panel to help students plan for their future jobs (1978 Disability Awareness Week Flyer). In 1979, workshops such as “Communicating with Hearing Impaired Persons” and “A Chance to Love: Sexuality and Physical Disability” were offered. Performances by the Fairmount Theatre for the Deaf were added to the programming lineup as well. Along with this shift in programming came a shift in the title from “Understanding Disability and Physical Difference Month” to “Disability Awareness Month” (Challenge Newsletter Spring 1979).

As we look back on the Disability Awareness Month festivities, take time to also reflect back on the great strides that have been taken since that initial signing of Section 504 fifty years ago. The Disability Awareness Month we know today has evolved from initially spreading awareness that disabilities and physical differences existed to celebrating the rights that have been won and continue to be won through disability activism and legislation.

*All historical photos courtesy of the

Check out this Disability Awareness Month flyer from 1973 in the Library's Special Collections and Archives!